Triumph

and Sadness:

Opposites in Ourselves and in

Nat Fein's Photo of Babe Ruth's Farewell

By Michael Palmer

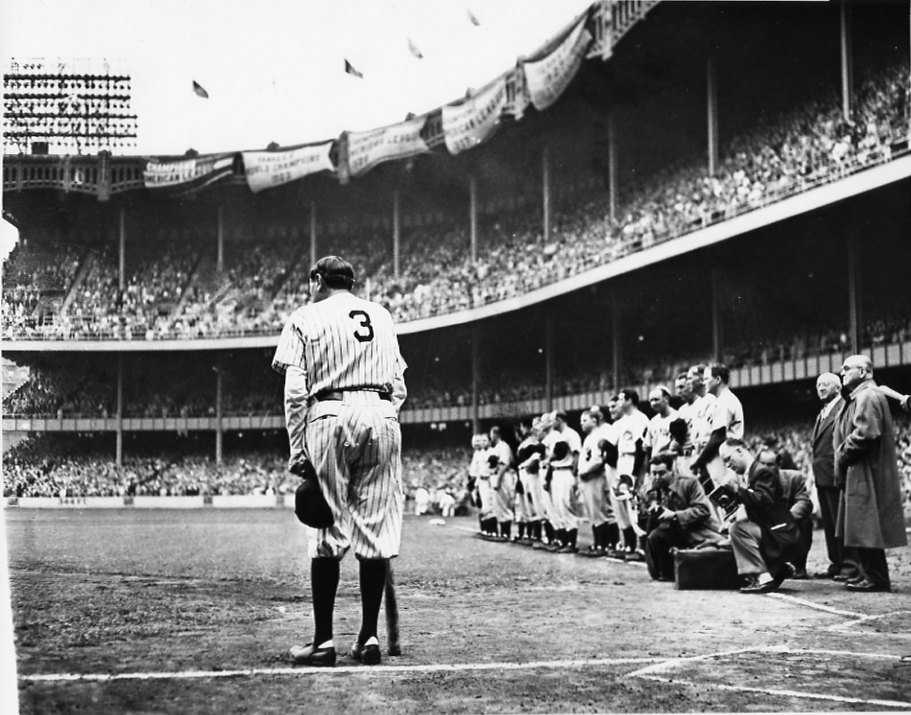

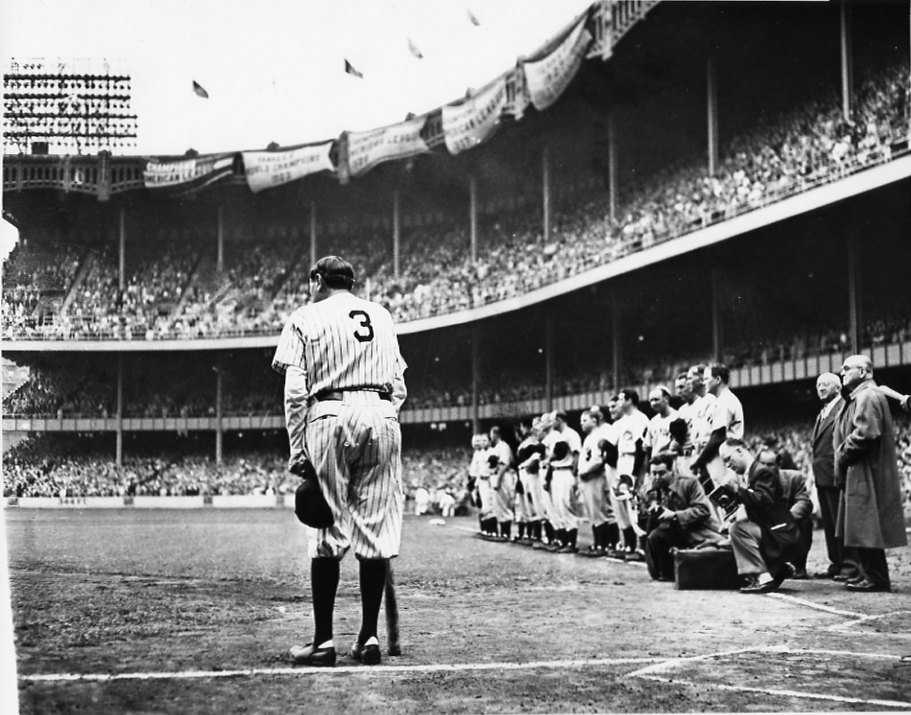

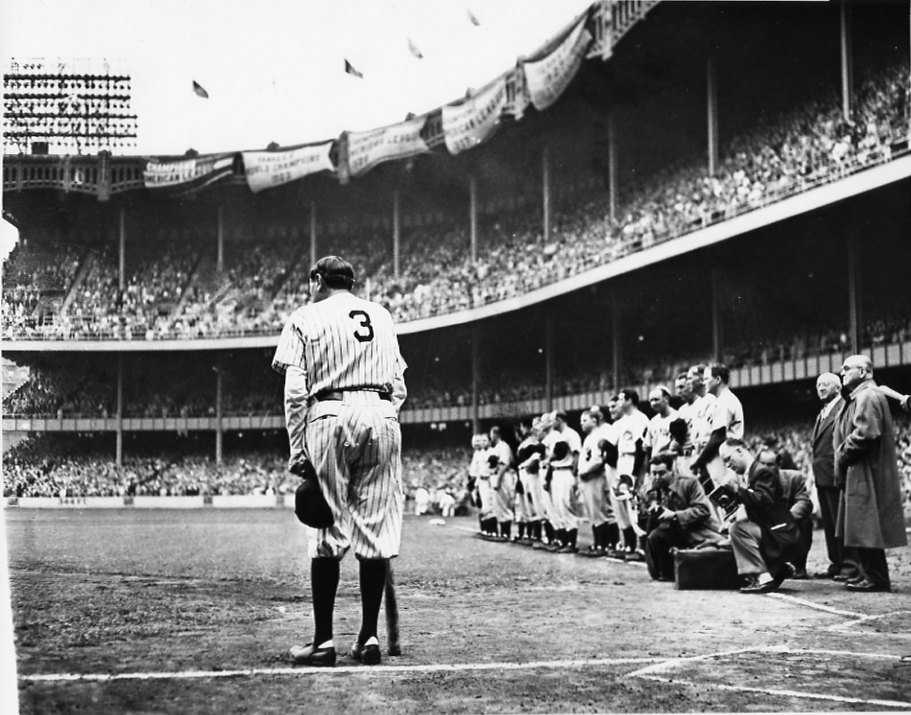

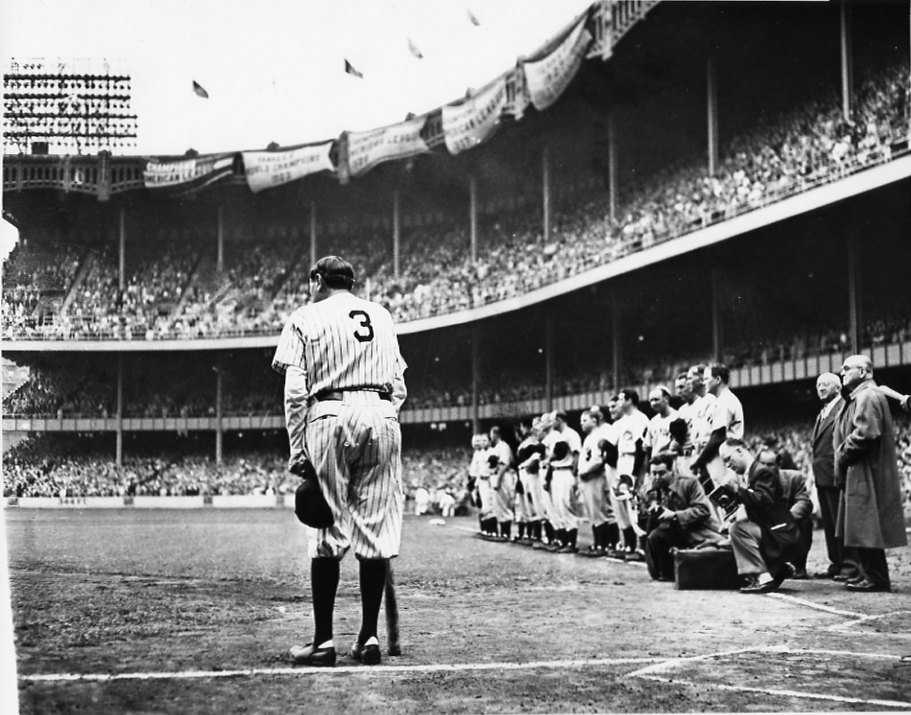

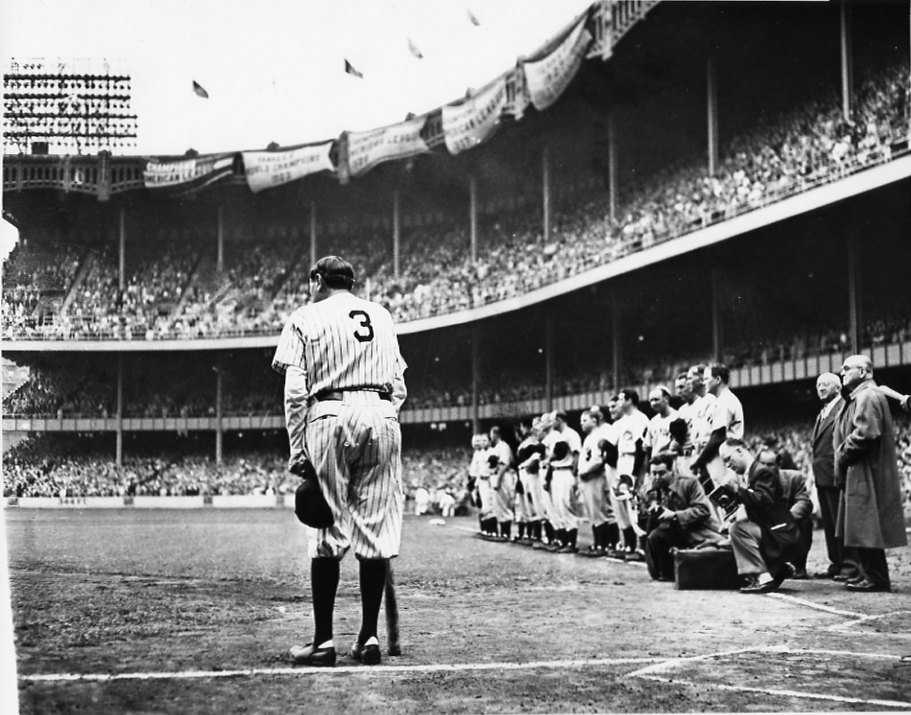

This photograph taken by Nat Fein of baseball's legendary George Herman

"Babe" Ruth is one of the most famous and most cared for in all of sports.

It won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949.

I'm moved each time

I see it because it has great feeling—a man returning to the scene of his

greatest successes, saying goodbye for the final time. The way triumph

and sadness, pride and humility are one in this photograph give it a meaning

that goes far beyond the story it tells as a newspaper illustration.

I am grateful to Aesthetic Realism,

the education founded by the American poet and critic Eli

Siegel, to have a method of understanding why I care for this photograph.

It is in his great principle—"All beauty is a making one of opposites,

and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves."

In its technique this photograph puts together opposites people are trying

to make sense of in their lives such as:

1.

Triumph and Sadness, Pride and Humility

The photograph was taken

at Yankee Stadium on a special day for the Yankees and Babe Ruth—the 25th

anniversary of the Stadium. Ruth, who had left the Yankees as a player

14 years earlier, was having his famous number 3 uniform retired.

The idol of millions whose homerun hitting, personality and flair literally

built Yankee Stadium and made him baseball's greatest figure, Babe Ruth,

here, was a very sick man who had barely two months to live. Nat

Fein, a staff photographer for the New York Herald Tribune,  was

looking for a picture that would convey the meaning of that day.

He left the other photographers and went to the back of where Ruth was

standing, where he saw the elements of the story in one composition—Ruth

in relation to his former teammates, to the Stadium, to the fans.

He saw Babe Ruth in a moment of great triumph and in a tremendously sad

moment as well. was

looking for a picture that would convey the meaning of that day.

He left the other photographers and went to the back of where Ruth was

standing, where he saw the elements of the story in one composition—Ruth

in relation to his former teammates, to the Stadium, to the fans.

He saw Babe Ruth in a moment of great triumph and in a tremendously sad

moment as well.

Though it was an overcast day, Fein took the picture without a flashbulb

because he believed what he learned from his picture-editor, Richard Crandall,

to be true—"natural light catches the mood of the occasion."1

The mingling of light and dark captures accurately the mingled feelings

of that moment. Ruth himself is light and dark—his light uniform

set off by the dark socks and hat and dark pinstripes on the uniform.

Light crowns his dark hair. The fans in the distant Stadium seats

are also light and dark—the persons in the visible seats are illuminated,

while darkness shrouds those sitting farther back. That combination

accents the poignancy felt by people on that day.

In a published lecture titled Afternoon Regard for Photography,

Eli Siegel took up a photograph related to this one—a Dutch actor seen

from the back, bowing in his farewell to an audience in Amsterdam.

What he said explains a central reason other people have been so much affected

by the Nat Fein photo. Said Mr. Siegel:

Pride

is in the fact that he is the hero of the evening, he is acknowl- edging

applause...[and] this man is [also] an object of sadness—as in every farewell.

We are trying to put our triumph and our sadness together. 2

This, I have learned, is

what art does. People most often see the world in two ways and I

did. I felt there was the world in which my team won the pennant,

and there was another world, as I saw it, in which everything came to a

sad ending. I would say to myself—"A hundred years from now what

will it all matter?" Dividing the world in this way is inaccurate;

it is a form of what Aesthetic Realism describes as contempt, the “disposition

in every person to think he will be for himself by making less of the outside

world.” It is the same world, I have learned, that gives us triumph

and tears, sadness and joy.

Babe Ruth here is tall, the largest figure in the picture. He has

grandeur. Yet he is humble too, slightly stooped at the shoulders, his

hat at his side. And above Ruth's head, flags fly on tall poles atop

the Stadium.  The

pennant banners blowing in the wind rise, while they also have uncertainty.

The facade on the upper deck on the right, crossing behind the figure of

Ruth, sweeps up, giving his hunched shoulders an upward motion. The

pennant banners blowing in the wind rise, while they also have uncertainty.

The facade on the upper deck on the right, crossing behind the figure of

Ruth, sweeps up, giving his hunched shoulders an upward motion.

Though very young, I was at the Stadium that day in 1948 and I remember

being both thrilled at seeing Babe Ruth in uniform and saddened by the

obvious weakening his illness had made for. Ruth, in his final words

to the fans, said he was grateful for having been part of something whose

large meaning goes beyond the playing field. This can be felt in the way

he stands. He is bowing slightly, his cap to his side. He is both the center,

being honored, but is also honoring something outside of himself, looking

out to the encircling stands and to the open spaces, the infinite beyond

the Stadium.

2.

We Are an Individual and We Are in Relation.

In his book Self

and World, Mr. Siegel describes the largest question a man has—how

to be oneself as individual, and at the same time be in the best relation

to what is not oneself. He writes:

We are

alone in our blood and our bones and our thoughts. It seems we are

separate, if we want to feel that way.

And yet we can look out. Not a thing fails to act on us, once we

think about it. 3

Babe Ruth, alone here in

the center of the Stadium, is shown looking out, and through the composition,

not a thing fails to act on him. His body joins the playing field

and the three decks of the right field stands—the very area where he hit

so many of his homeruns. The curving, horizontal facades of the lower,

middle, and upper decks cross the vertical of his body. The vertical

figure of Ruth is alone and also at one with Stadium and fans.

The way I saw being an individual was very narrow and against my being

in a good relation with the world. It was a cause of much pain.

I thought I was most myself by being as separate from people as I could

be, and didn't like doing things other children did, such as going to parties,

dances, summer camp. I preferred taking long walks by myself, and

when I went to a ballgame, I liked going alone, sitting by myself, way

on top, away from the other fans. I was triumphantly alone, but very lonely.

This way of seeing changed as I studied in classes taught by Eli Siegel.

Seeing how I was hurting my life, Mr. Siegel said to me in a class:

A human

being, according to Aesthetic Realism, has an indefinite possibility of

conscious relation. That can be felt in the line from Tennyson's

[poem] "Ulysses"—"I am a part of all that I have met." But Ulysses

could also say, "I am a part of all that I haven't met." Do you want to

come into your heritage? Your heritage is all reality besides yourself

as seen by you.

I love Mr. Siegel for his

understanding of what I was hoping for, and I’m tremendously grateful for

the deep friendships and full life I have now and for my happy marriage

to Lynette Abel. I wish Babe Ruth could have learned what I have

learned, which I believe he longed for.

In this photo, the great Babe Ruth is shown in relation to the world in

many ways. The bat he is holding and leaning on almost seems a part of

his body. The vertical stripes of his uniform are related to the vertical

lines of the middle deck facade and the vertical poles of the Stadium throughout.

The field and the baselines link him to former teammates and other Yankee

players. You feel Ruth is "a part of all that he has met and all

he hasn't met."

__________________________________________

Notes:

1. John Faber,

Great

News Photos and the Stories Behind Them. (New York: Dover Publications,

1978), 102

2. Eli

Siegel, Afternoon Regard for Photography, Excerpts from Eli Siegel’s

Discussion of Photography from the Aesthetic Realism Point of View.

(New York: Aesthetic Realism Foundation, 1967), 10

3. Eli Siegel, Self

and World, An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism, (New York: Definition

Press, 1981), 102 |