Aesthetic

Realism seminar:

What's Real Intelligence—about the World

and Ourselves?

with a discussion of Samuel Leibowitz

& the Scottsboro Case

By Michael Palmer

Growing up in the

Bronx, I was affected early by my father and older brother's enthusiasm

for sports and popular music, and I admired persons who seemed to look

out for others such as Knicks basketball star Dick McGuire who loved setting

up teammates for easy baskets, even more than shooting himself. And

at a stage show my father took me to, I remember being thrilled by trumpeters

Charley Shavers and Ziggy Elman driving the Tommy Dorsey band in a swinging

instrumental, then providing a mellow background for the band's singer.

I also loved watching Perry Mason on T.V. using his legal knowledge to

clear people who'd been wrongly accused. They were showing what Mr.

Siegel explained in his lecture Mind and Intelligence is essential

for real intelligence:

"We want to

be smart about how to take care of ourselves, but we also have to do a

good job with everything else."

But as I had to

do with people every day, my focus was not on caring for them, but on myself.

I avidly studied sports, and became a whiz on players’ records and little-known

facts, and my father liked bragging to friends, "Ask him anything about

sports,” And when Benny Schwartz asked, "How many games did Jack Chesboro

win in 1904?, and I answered,"41," I felt I was wonderful. Meanwhile, Benny's

life mattered little. He existed to admire my "intelligence." Mr.

Siegel explained:

" To be intelligent

means to have an ability to know not just one kind of thing, but those

things that life in its uncertainty, richness and variety can bring up."

As I was specializing in

the minutiae of sports at the expense of everything else-especially the

feelings of people-life’s “richness and variety” was passing me by.

Later, as a first baseman on my P.A.L baseball team, I liked helping my

teammates, pulling in a high throw from shortstop, scooping up a low throw

from third, but, in my quiet way, I also wanted to be the star. In

a game for the city championship, I made a stupid decision. I ignored a

bunt signal, swinging away instead, ruining a rally. After being

deservedly benched, I was so angry I secretly hoped my team would lose.

So while I gave the appearance of being a nice guy, I knew I wasn’t.

I had little or no feeling for other people and I didn’t respect myself.

I was in the midst of what Mr. Siegel describes in his lecture:

"The first

thing that we do, bad for intelligence is separation. For example, people

want to take care of themselves, and they also want to be nice people."

After college, when

I got a job writing sports at WCBS Radio, I thought I had made it, being

there as the news of the world was coming in, but I used that to be even

colder to the feelings of people. Our country was in Vietnam, brutally

trying to impose an economic system on people who did not want it.

I had no feeling for the suffering of the Vietnamese, and was annoyed with

war protesters here for causing so much "trouble in getting around town."

When I wasn’t working, I preferred being by myself, playing golf, going

for long walks, feeling that other people would surely interfere with my

reverie and routines. I felt lonely, empty, and soon began having mysterious

panic attacks that had me quite worried. Several years later in a

class I attended taught by Eli Siegel early in my study he asked me, "Are

you as nice a guy as you'd like to be?

MP:

I think my attitude could be better to people.

ES: Well,

can you be against them?

I was. I was competitive

with people, secretly hoping they wouldn’t do well, so I’d look better,

and I was certain they felt the same way. Mr. Siegel, saw I was against

myself for this attitude and he asked me, “How do you want to see yourself?

I answered: “I want to approve of myself.”

ES:

Good, how are you going to do it? There are many persons who are

going to concerts tonight. Their purpose is to see themselves better.

The thing is, what does it mean to see oneself well? To see oneself

well has two departments. You can say, 1) I am Michael Palmer, and

2),, I am also how I am related to all things.

Relation was a new way

of thinking for me! Studying Aesthetic Realism, I began to see how

I was related to things through the art and literature of the world.

For instance, in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, through how

Pip and his roommate encouraged each other, I was learning how I wanted

to be with other people! In James Fenimore Cooper’s The Deerslayer,

Natty Bumppo showed that being ethical and fighting for justice made a

man strong and also wise; and reading Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice,

I was thrilled by Elizabeth Bennet’s criticism of Darcy, seeing that a

woman could sincerely want to have a good effect on a man. I was

learning what it means to have good will, which is the greatest intelligence.

And in time, I came to care deeply for a woman, Lynette Abel, whose feeling

for people, for justice, her kind criticism, has me more related to the

world every day and I love her for it! I’m grateful for our happy marriage

of more than 11 years.

What Was Real Intelligence

for a Noted Attorney?

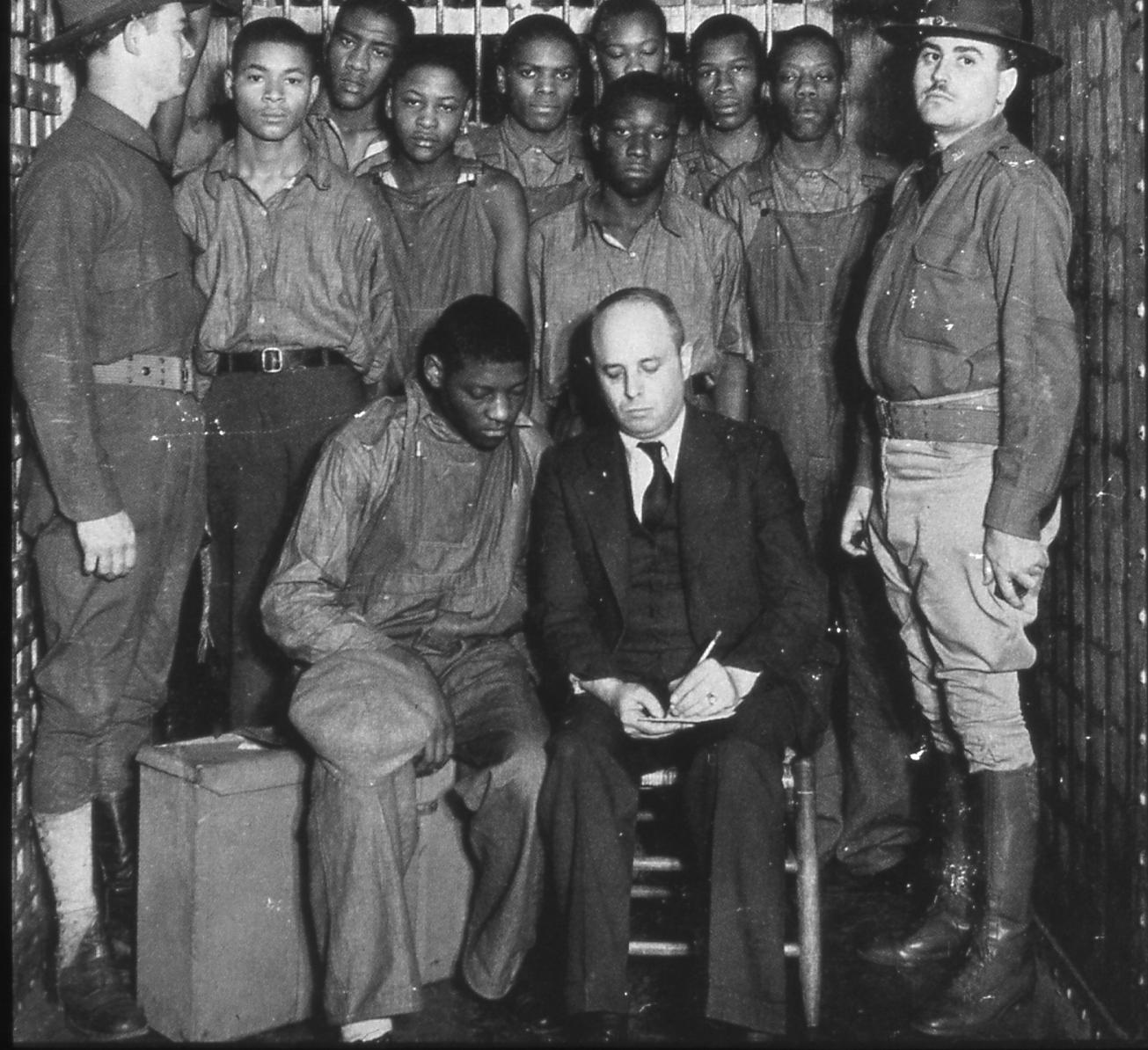

I speak now about one

of the most successful criminal lawyers of the 20th century,  Brooklyn's

Samuel Leibowitz, who, amazingly, lost only once in 140 murder cases, but

is best remembered for his defense of the so-called "Scottsboro Boys," Brooklyn's

Samuel Leibowitz, who, amazingly, lost only once in 140 murder cases, but

is best remembered for his defense of the so-called "Scottsboro Boys," which would inspire the civil rights struggle in the South in the crucial

decades to come.

which would inspire the civil rights struggle in the South in the crucial

decades to come.

Born in Romania

in 1893, Leibowitz came to this country at the age of 4. His parents, like

other immigrants on the lower East Side, began with little, but his father

did well enough to move the family to Brooklyn, and eventually enable his

son to go on to college and law school. Though Samuel's first love was

baseball—his Dodgers—he also cared for dramatics and debate, and would

eventually choose criminal law, feeling that was how he'd best make a living.

Though Leibowitz, as biographer Quentin Reynolds described him, “had none

of the dedicated qualities of a Clarence Darrow to joust against injustice,”

he knew the law and literally "lived" with a case 24 hours a day. With

each success, word got around--he was the man to turn to if you were in

trouble. Stated Mr. Siegel,"Intelligence means learning; learning is a

taking by the self of the new with a love for the old." As a criminal lawyer,

Leibowitz had to welcome both the new and old. As he said, "I've had to

study…every conceivable scientific subject from ballistics to serology

(blood makeup).”

For

part 2 click here

|