Aesthetic

Realism seminar:

What's Real Intelligence--about the World and Ourselves?,

conclusion

with

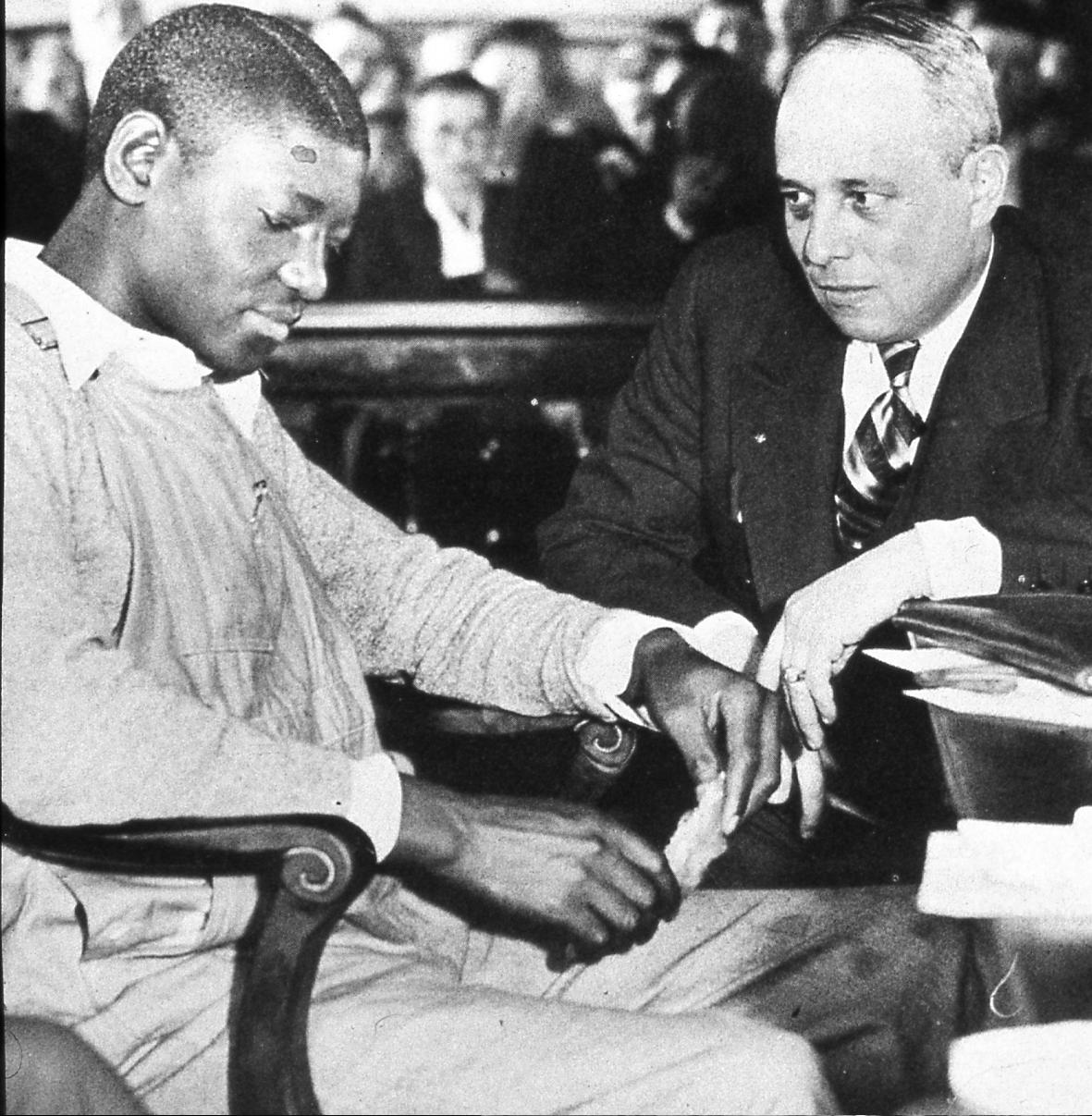

a discussion of Samuel Leibowitz

& the Scottsboro Case

By

Michael Palmer

Alabama “justice”

was swift. It took only two weeks for individual trials to begin, and with

angry crowds chanting and singing, "There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town

Tonight" outside the courtroom, and the accused men represented by two

incompetent lawyers, the first two Scottsboro defendants were convicted

and sentenced to death. But, there was an appeal, and the Supreme Court

reversed the convictions, ordering new trials.

Defense of the young men was organized by The International Labor Defense,

and for the new trials, they wanted the nation’s best known lawyer, Clarence

Darrow, but now in his 70's, he was not up to it. So, they tried

for the next best, Samuel Leibowitz, a Jew from Brooklyn--who, astoundingly,

would be asked to go to the deep South to defend the young Black men. “Intelligence,”

Mr. Siegel said, “has to do with a love for the happening as fact. We want,

when intelligent, to make the fact beautifully ours.” Knowing it was a

longshot and that they likely couldn’t afford him, the I.L.D. appealed

to Leibowitz’s “love for the happening as fact.” They wrote to him:

" You will

not only be representing nine innocent boys, you will be representing a

nation of twelve millions of oppressed people struggling against dehumanizing

inequalities."

Leibowitz had many lucrative

cases waiting at home. He could have easily said ‘no,’ but this met something

deep in him—a chance to be clearly useful. He wrote back that as a “Brooklyn

Democrat” he didn’t agree with the political views of the I.D.L.,which

were of the Left, “But this,” he said:

"is about the

basic rights of man. If I serve this cause, as you suggest…I will not serve

it for money, nor will I permit you to repay any expense I may incur."

Leibowitz was "in." He had never been to the South, but on his first visit

to Scottsboro he got a taste of what he'd be facing. The people wanted

what they called "justice." In other words, they wanted the defendants

hanged to teach all Black people a lesson. Never in his career had he faced

anything like this. He decided his best chance would be to challenge

the system of jury selection in Alabama that had excluded all Black persons.

He saw to it that about a dozen Black people appear for jury selection—the

first time this had been done in the South. Among them was a 55-year

old man, John Sanford, whom the Attorney-General Thomas Knight immediately

began to question in an angry patronizing way, pointing a finger directly

at Sanford's face, saying, "Now John…” At this point, Leibowitz snapped,

"Please move away from the witness, take your finger out of his eye and

call him, Mister Sanford." From this moment on, feeling ran high against

Leibowitz who had the nerve to ask Knight to call a Black man 'Mister."

There were death threats against him. The National Guard was called

out to protect Leibowitz and his wife, Belle. One man was heard to remark,

"It'll be a wonder if he leaves this town alive." But Leibowitz had a large

purpose and he seemed to take on more courage.

In

the trial of the first defendant,  Heywood

Patterson, the doctor who examined the women after the charges had been

made, testified that neither showed any evidence that a rape had occurred.

And one of the women, Ruby Bates, actually testified that she was told

to frame the defendants to avoid a morals charge against herself.

Despite this, the all-white jury came in laughing with a guilty verdict

against Patterson. But in a surprise two months later, Judge John

Horton set aside the verdict saying the evidence did not support it. His

courage would cost him his judgeship in the next election. Heywood

Patterson, the doctor who examined the women after the charges had been

made, testified that neither showed any evidence that a rape had occurred.

And one of the women, Ruby Bates, actually testified that she was told

to frame the defendants to avoid a morals charge against herself.

Despite this, the all-white jury came in laughing with a guilty verdict

against Patterson. But in a surprise two months later, Judge John

Horton set aside the verdict saying the evidence did not support it. His

courage would cost him his judgeship in the next election.

The

trials continued in the next year with a new, segregationist Judge, and

despite the lack of evidence, guilty verdicts were returned against the

first two defendants. In his lecture, Mr. Siegel said, “intelligence can

be defined as the ability to take care of oneself and also to care as such.”

Terribly frustrated, Leibowitz could have easily given up at this point,

but defiantly, he said, "These young men are absolutely framed. I'll fight

till hell freezes over to save them!"

Intelligence

in the Nation's Highest Court

In January, 1935,

Samuel Leibowitz took the Scottsboro Case to the Supreme Court. For

the first time in his career he was nervous. A criminal lawyer rarely appeared

before the High Court. And he was told his usual emotional approach

wouldn’t work here—the Justices were only interested in constitutional

law. “To want the new,” said Mr. Siegel, ”to want to be at home in it,

is a measure of intelligence in the most thorough sense.” Leibowitz met

“the new” with relish, arguing that although Alabama law did not state

that Black persons be barred from jury duty, actual jury selection

did exclude them and this was unconstitutional. He told the Court

that names of six Black persons had been forged on jury rolls after the

first trial. Forgetting the warning about emotion he said passionately,

"This is fraud, not only against the defendants but against the very Court

itself." "Can you prove this forgery?, Chief Justice Charles Evan Hughes

snapped."I can Your Honor," Leibowitz said, "I have the Jury rolls here

with me." The Chief Justice bent over the pages. Finally he raised

his head, "It's as plain as daylight," he said as he passed it to Justice

Louis Brandeis, then to Justice Benjamin Cardozo, and the others.

Six weeks later, the court handed down a unanimous opinion—Black people

had been barred from jury duty, the convictions were reversed and new trials

ordered. Said Leibowitz,"I am thrilled beyond words."

But, a year later, Alabama convicted four of the Scottsboro defendents

for a fourth time, though dropping the death penalty for life sentences.

And 12 Black people were interviewed for the Jury--the first time that

had happened in the South since reconstruction days. Leibowitz had brought

the 14th amendment—due process for all citizens--to life in the South.

Then, a shocking development--Alabama dropped rape charges against the

five remaining defendants--four to be released immediately. Elated,

Leibowitz knew he still had to get them out of Alabama safely. A sullen

crowd gathered near the jail. “Intelligence,” Mr. Siegel stated “is the

ability of the self to become at one with the new.” Leibowitz had to quickly

become one with this new situation. He secretly arranged for two cars to

be at the back of the jail. He got the young men in the cars and they all

sped away from the crowd. They didn't breathe freely until they had crossed

the Alabama-Tennessee border, then onto a train bound for New York's Grand

Central Station. There, they were met by a mob, but not the kind they had

feared all those years-—there were 20 thousand, happy, cheering people

welcoming them to New York. Within the next decade, the remaining

Scottsboro defendants were also freed, albeit suffering from the effects

of the time spent in horrible Alabama jails.

Some years later, in 1949, Leibowitz, well into his second career as a

Judge in Brooklyn's Criminal Court, was in Ebbets Field watching his Dodgers

when he was asked by biographer Reynolds, “Judge, What did the Scottsboro

Case mean to you?” Pointing to Jackie Robinson, the first African-American

to play in the major leagues, he said, "Baseball wasn't worthy to be called

our national game until Black people had every right to play in the big

leagues." And he added, "I like to watch Jackie playing alongside

Pee Wee Reese of Louisville, Kentucky, each encouraging the other.

I feel they’re molding a new and fine tradition. Yes, I think I had

a little to do with that, and that's what the Scottsboro case means to

me."

Real intelligence, Aesthetic Realism shows, is that beautiful oneness of

justice to humanity and ourselves. It has never been needed more in the

world than now!

Return

to beginning

|